Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, the student will be able to apply vector analysis to estimate forces on a structural member.

Next Generation Science Standards

- NGSS HS-ETS1-2 “Design a solution to a complex real-world problem by breaking it down into smaller, more manageable problems that can be solved through engineering”

Common Core State Standards

- CCSS.Math.Practice.MP1 “Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them”

- CCSS.Math.Practice.MP4 “Model with mathematics”

Supplies

- Ruler

- Balsa wood sticks

- Balsa wood sheets

- Pins

- Wood glue

- Knife (see teacher or parent)

- Spring balance

- Bubble level

- Bridge you built in Basics of Structural Engineering Part 1

- Safety glasses

Units Used

- Mass: kilogram (kg)

- Length: meter (m)

- Time: second (s)

- Force: Newton (N) (1 N=1 kg m/s2)

Part A: Vector Analysis

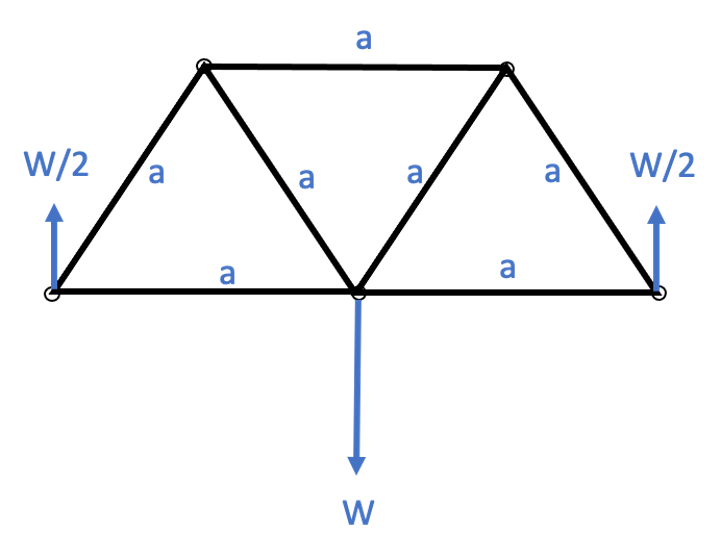

In the last lesson, we built a truss that looked like this, and found that the reaction forces R1 and R2 were each equal to half the applied weight W.

What if we needed to know the forces in each of those balsa wood members? Perhaps we want to figure out if we’ve opted for thick enough sections of wood to handle the weight we plan to apply, for example. They key to figuring out these loads are to use vectors! Recall, vectors have both magnitude and direction; and forces are a vector quantity. The weight applied is a vector acting downwards. The reaction forces are vectors acting upwards. The balsa wood members are helping carry the load – that means there are forces on those members in either tension, pulling on the member, or compression, pushing it together, which can be written as vectors aligned with the members. For example, if I want to solve for the forces in the members on the left-hand side, I can cut an imaginary slice in the truss, shown on the free body diagram below in red, to expose those forces.

Now my diagram looks like this:

I can solve for the forces by writing Newton’s law, that the sum of the forces is zero (the bridge still hasn’t flown away), and by accounting for the vertical direction and horizontal direction separately (the bridge isn’t flying away vertically, nor is it flying away horizontally). In the vertical direction, I only have two forces on my diagram, W/2 and F1. W/2 is entirely vertical, and F1 is at a 60 degree angle (recall this is an equilateral triangle). From trigonometry, we can then find the vertical component of F1 as F1sin(60). Summing forces in the vertical direction to find an equilibrium equation gives us:

W/2+F1sin(60)=0

Which means:

F1=-(W/2)(1/sin(60))=-W/√3

Wait, so there’s a minus sign there? That means that instead of pulling on that member, which mean it is in tension, the structure is pushing on that member, so it is in compression! We can now look at all the forces in the horizontal direction to find F2. Looking back at our figure, the only forces in the horizontal direction are F1 and F2. Our equilibrium equation in this horizontal direction is:

F1cos(60)+F2=0

Since we’ve already solved for F1 in terms of W, we can solve for F2 now as:

F2=-F1cos(60)=-(-W/√3)(1/2)=W/(2√3)

This is a positive value, so that horizontal member is in tension! Cool, right, so now I know that if I add 5 Newtons of weight, W, to my bridge at its midpoint, then those two members need to be strong enough to be able to carry:

F1= _____N

F2= _____N

With these skills in vectors, geometry, and trigonometry, you can extend this to analyze the complicated trusses you see all around you.

Part B: Biological Inspiration

Ok, that was a lot of math. Let’s take a break and go for a walk. But, your tasking for your walk is to look for how nature creates junctions of structures. Look, for example, at how a bug’s legs meet at its abdomen, or how a flower’s stem supports its bloom. Take pictures if you can, and when you get back, sketch some of what you saw.

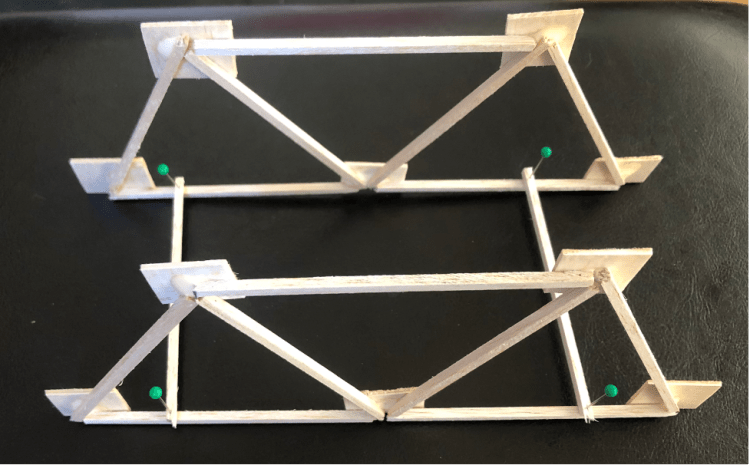

Part C: Gusset Plates

What sort of connections did you find on your nature walk? I suspect you often found some type of central support to help transfer load. For example, an ant’s legs do not connect directly to each other, but instead join at its body, which helps support the entirety of the structure. In engineering the equivalent to this is a gusset plate. Gusset plates are what you see the various members of a truss connected too. This helps transfer load and add strength. To see this for yourself, pull out the bridge that you built in the first structures lesson. Build a second one using gusset plates using the balsa wood sheets in your kit. Cutting a small square of balsa wood sheet will work as a gusset plate for this bridge. You may find a combination of pins and wood glue to be optimal for securing your bridge.

Let’s see which one is stronger, this is the fun part – time to put on your safety glasses. Set both bridges up covering a similar span. Start adding weight to each of them until they break. Which one held longer?

Bonus: Fishy Analogue

A fishy analogue to a bridge’s gusset plates could be the hypural plate that helps join the fish’s spine to its tail. Using the balsa wood components you have, devise your own fish tail structure. How would you connect this tail to your BLIMP hulls?

Last updated May 23, 2022.