Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, the student will be able to model physical systems with free body diagrams and to use that model to formulate static equations of equilibrium for trusses.

Next Generation Science Standards

- NGSS HS-ETS1-2 “Design a solution to a complex real-world problem by breaking it down into smaller, more manageable problems that can be solved through engineering”

Common Core State Standards

- CCSS.Math.Practice.MP1 “Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them”

- CCSS.Math.Practice.MP4 “Model with mathematics”

Supplies

- Ruler

- Balsa wood sticks

- Pins

- Knife (see teacher or parent)

- Scale

- Spring balance

- Bubble level

Units Used

- Mass: kilogram (kg)

- Length: inch (in)

- Length: centimeter (cm)

- Length: meter (m)

- Time: second (s)

- Force: Newton (N) (1 N=1 kg m/s2)

Part A: What is a free body diagram

The very first step in solving structural engineering problems is to draw what is known as a free-body-diagram. If you have taken physics, you may have done this already! This is a simple process and is very helpful in modeling physical systems. Let’s start with an example, picture a car. Draw a sketch of the car you’re picturing (do not worry if art is not your thing, the goal here is to capture the physics, this is not an art contest).

Now draw arrows to represent the vectors (magnitude and direction) of the forces that act on the car. For example, the car has weight, so you should have a vector pointed downward. But the car doesn’t fall through the ground, so there is a normal force from the earth upwards on the car that balances out weight. Is your car moving? If so, then there is probably a force between the tires and the road. Similarly, there’s friction between the tires and the road acting in the opposite direction along with air drag. Is your car accelerating? Newton’s second law says the sum of the forces on a body equal’s the body’s mass times its acceleration. So, if the body is accelerating, then the force between the tires and the road should be larger than the drag and frictional forces. Need a little practice with this? Check out the Free Body Diagram Interactive at: https://www.physicsclassroom.com/Physics-Interactives/Newtons-Laws/Free-Body-Diagrams/Free-Body-Diagram-Interactive.

Part B: Trusses

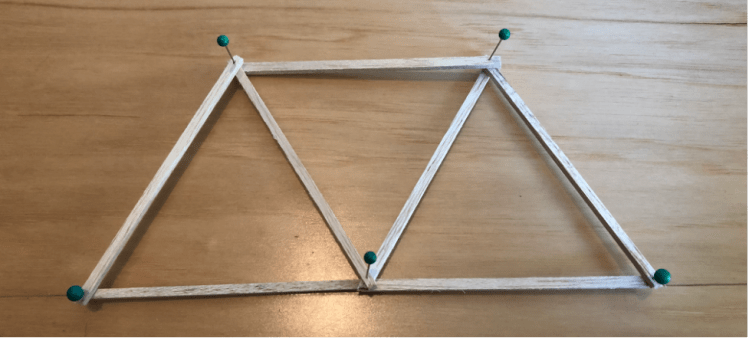

Have you ever built a bridge out of toothpicks, straws, or balsa wood? That was a truss – an assembly that uses beams and simple connections, often leveraging triangular geometries, to make a remarkably strong structure. Trusses are all around you, in your attic, holding up bridges, and supporting vehicle structures. Get the balsa wood sticks and pins from your BLIMP kit, we are going to build a truss. Let’s start with making two equilateral triangles – recall an equilateral triangle has the same length on all sides. I measured and cut 4-inch (~10 cm) segments of balsa wood and pinned them together like so:

Next, we are going to connect these two equilateral triangles with a cross bar at the top and the pin at the bottom into a structure that look like this:

You now have a bridge. It’s probably a fairly floppy bridge though. Let’s extend it into three-dimensions by building a second identical truss, and connecting the two of them cross wise with balsa wood as well. Your final product should look something like this:

Now let’s put that bridge to work and exercise your understanding of free body diagrams.

Part C: Truss Analysis

If you added weight at the bottom center node, can you calculate the reaction forces at the ends? If you’re unsure how to do this, start by drawing a free body diagram of your bridge with the weight added. Then, we can use what we know of forces and moments to solve. For example, a free body diagram of your bridge, with the added weight, might look something like this, where R1 and R2 are reaction forces at the ends, and a is the length of each truss member.

Again, Newton’s second law says the sum of the forces on a body equal’s the body’s mass times its acceleration, but this truss is not flying away, it is static, so the sum of the forces on the truss should equal zero. Forces are vectors – they have magnitude and direction. In this case we have three forces, R1 and R2 acting upwards and W acting downwards. So:

R1+R2-W=0

That’s great, but we still have two unknown reaction forces, R1 and R2. So, we need a second equation. Not only is this truss not flying away, it’s not spinning. We can calculate the moment on the truss from any given force about a specific point by calculating the force multiplied by the distance to the point of interest (the moment arm). So, let’s take the moment about that central node where the weight is applied. Because the weight goes right through the node, it has no moment arm, so the moment about that node due to the weight is 0. But, both R1 and R2 cause moments about the node, and because these trusses are built with identical equilateral triangles, R1 and R2 both act at equal distances from the central node, although they cause moments in opposite directions. This can be written mathematically as:

-aR1+aR2=0

This equation tells us that R1 and R2 must be equal! Going back to our force balance, that also tells us that both R1 and R2 must equal W/2. Let’s test our math with an experiment! Prop your bridge up with one end under books and the other end on a scale. Make sure it’s as close to level as possible; there’s a bubble level in your kit to help with this. Using the spring balance, pull down on the center node. Read the value off the spring balance; how much force are you applying? _______ N

Read the value of the scale at the end; how much force are you measuring? _______ N

Was the force at the end ½ what you applied?

Test your knowledge by repeating the same exercise only now with the force applied halfway between the end and the center. Draw a free body diagram. Update, as needed, the force and moment equations based on what you have in your free body diagram. What do you predict the reaction forces will be?

Prediction:

R1=______ N

R2=______ N

Now try the experiment; what do you measure the reaction forces to be? Note: you can get the reactions at both sides by flipping the location of the scale.

Measurement:

R1=______ N

R2=______ N

Did your values agree? Why or why not?

Bonus: Planes, Blimps, and the Aereon 26

Bridges are what many people first picture when they think of truss structures. But trusses are everywhere – including in blimps! For as long as the airplane has been around, engineers have used trusses to devise strong, light structures. Back in the 1960s, a company called Aereon Corporation sought to build lighter than air flying wing aircraft. Check out their patent number 3,129,911 “Framework for Rigid Aircraft.” Can you spot the trusses? If you enjoy non-fiction, you can learn about their flying wing aircraft, the Aereon 26, in the book The Deltoid Pumpkin Seed by John McPhee!

Footnote: Keep your bridge! You may want it for the next lesson.

Last updated May 23, 2022.